How I reduced (incremental) Rust compile times by up to 40%

At CodeRemote, I have forked and modified the Rust compiler, rustc itself. One feature — caching procedural macro expansion — has yielded 11-40% faster incremental build times in several real-life crates. That means faster dev builds and less laggy rust-analyzer (IDE IntelliSense).

If you’re a Rust compiler performance pro, feel free to skip to what I did. Otherwise, keep reading for more context!

Rust compilation can be slow…

There is a lot to like about the Rust language, but it’s a bit of a meme how frequent a complaint is compile time … so much so that “I’m feeling lucky” drops you into this poor guy’s support group:

While writing code, all developers want the shortest possible edit-compile-run cycle. Faster feedback = Higher productivity. While Go developers often take for granted their fast incremental builds, their Rust counterparts often take for granted their slow incremental builds — developing more learned helplessness than code.

Side note: What is an incremental build?

Say you just downloaded a Rust codebase and compiled it. That is a “clean build” since the compiler had to process that code from scratch.

Now say you already did a clean build, changed a couple lines, and then re-compiled. This is what I call an “incremental build”. In a day, a developer can do hundreds of incremental builds (repeat this cycle: make a code edit, compile, and sometimes run/test). Seconds add up fast.

Existing compiler options offer limited help with incremental build times

The good news: Rust offers many (often unstable) features that can optimize compiler behavior. Numerous blog posts1 2 3 in just the past few months cite a laundry list of configurations to reduce Rust compile times:

- Use the lld or mold linker

- Use the Cranelift codegen backend

- Build non-relocatable executables

- Strip debug info

- Enable the parallel frontend

- Use release (optimized) builds for procedural macro crates

The bad news: These options are of limited help with respect to incremental build times.

- Options 1 - 4 above optimize code generation. If you are building an executable (via

cargo build), these can help! Most developers (including myself), however, just want to know if their code can compile (i.e.cargo checkorcargo clippy) while coding. They are not interested in producing an executable, and thus codegen optimizations are of zero help. - Option 5 brings intraprocess parallelization. It can significantly speed up clean dev builds4 — provided of course that your machine has that enough CPU and memory. That said, personally I have noticed negligible improvement in incremental builds because the parallelized ‘analysis’ phase is far shorter than that in clean builds.

- Option 6 introduces an interesting premise: expanding procedural macros is slow! This solution comes at a tangible cost though, as a release build of a procedural macro crate is considerably slower than a dev build.

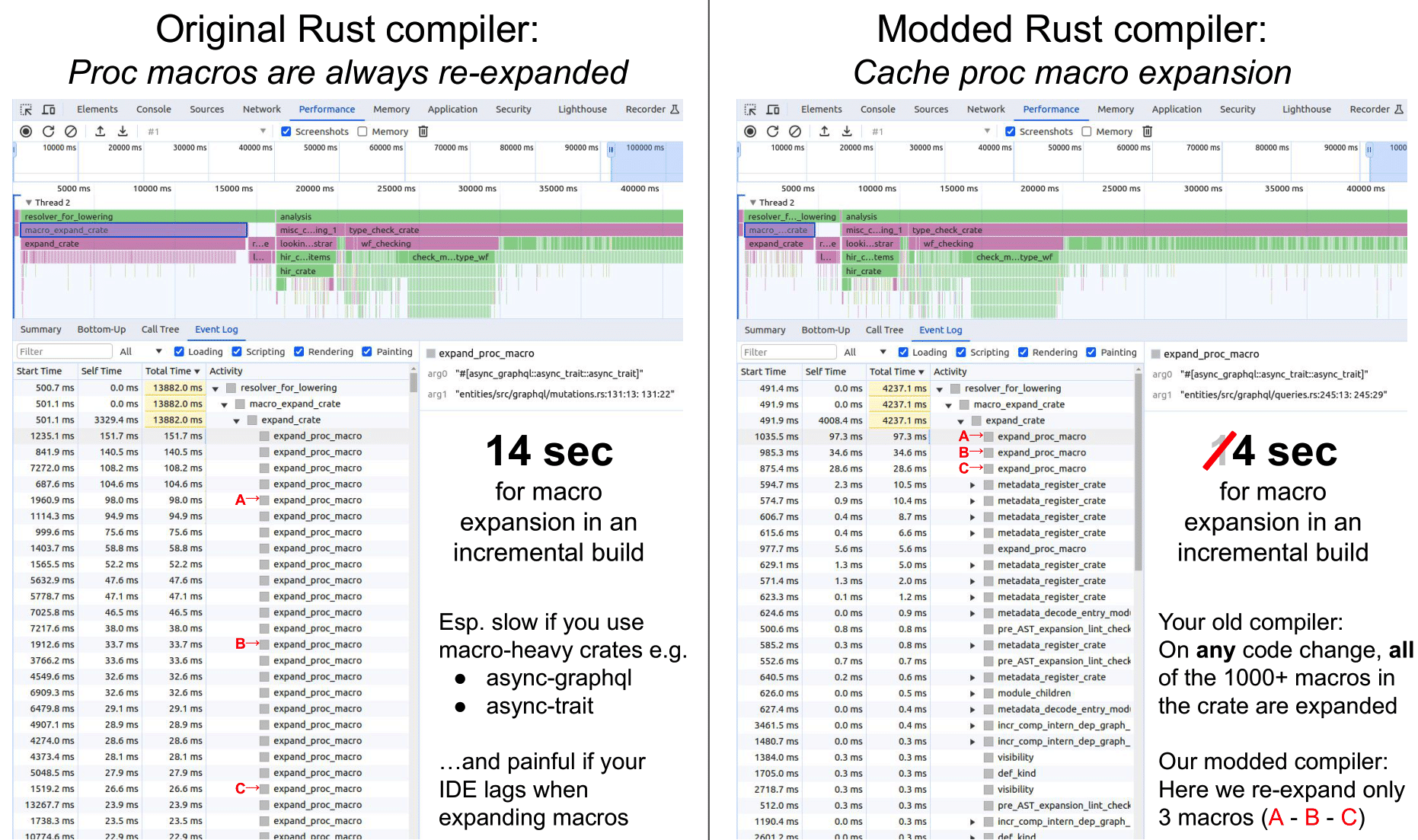

You’re probably spending considerable build time expanding procedural macros

Procedural macros are Rust ‘meta-functions’ that modify user-written code. Crudely, fn procmacro(user_code: string) -> /* output_code */ string.5 Executing this meta-function is called macro expansion, and macro_expand_crate (which you see in the profile at the top of this blog) is the very first step to compilation. Importantly, if you change a single line in your crate, all macros in that crate are expanded from scratch. Unlike the rest of the compiler,6 there is no caching here.

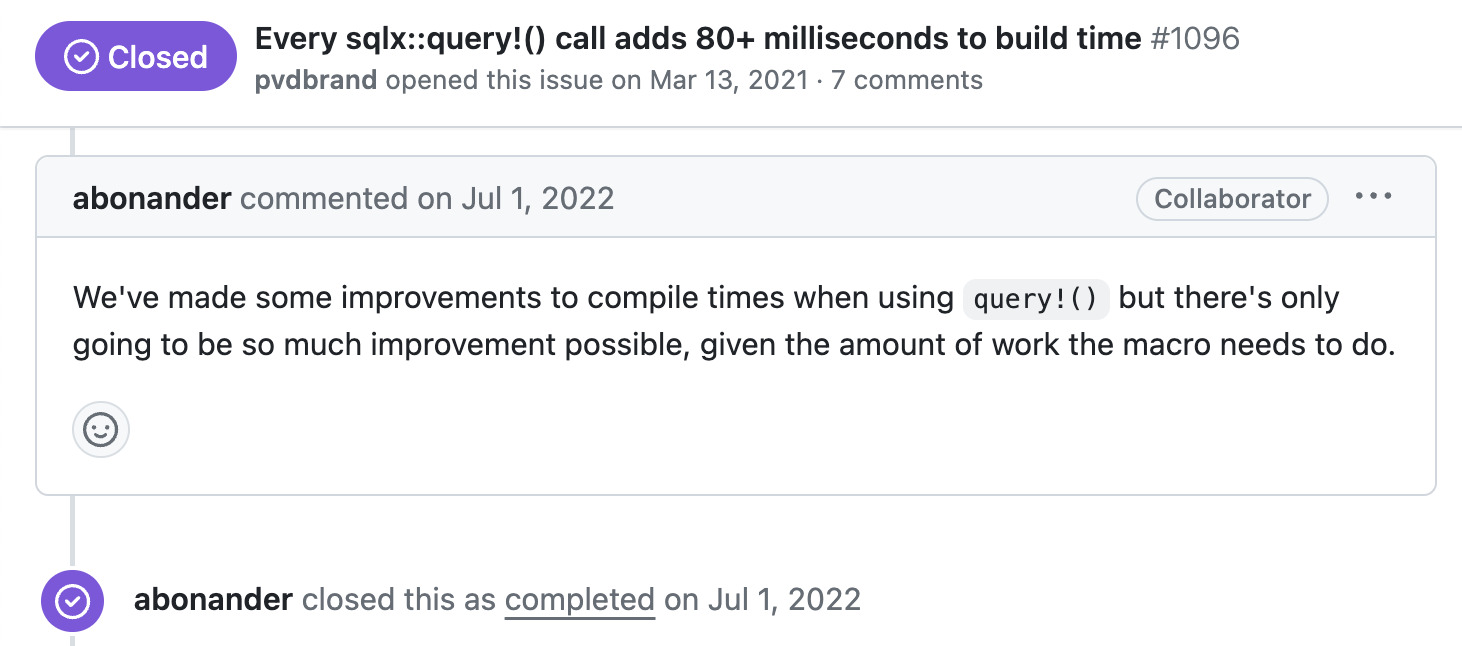

Why should you care? You likely don’t write (m)any procedural macros yourself, but I suspect they are used extensively in your crate dependencies. A few popular macro-heavy crates include serde, tokio, sqlx, actix-web, leptos, wasm-bindgen, async-[attributes / graphql / trait / stripe]. Long build times are a common talking point on these crates’ GitHub repositories: 7 8 9

tldr; slow macro expansion from your dependencies means slow builds for you.

Caching macro expansion: Up to 40% faster Rust incremental builds

There are many clever individuals and teams dedicated to holistically improving the Rust compiler. These days, the best improvements yield 1-2% faster builds on benchmarks.10. Unfortunately, a 1-2% improvement doesn’t mean much to a frustrated developer.

My approach: Project-specific focus on incremental build time

My approach, which is now the basis for CodeRemote, is necessarily different:

- I am singularly focused on shortening the edit-compile-run cycle. Goal: Make incremental dev builds fast.

- I want big (double-digit %) improvements on a few projects, not small improvements on many. Approach: Profile a project with painfully long incremental builds, understand the cause for slowness, fix it.

Methods: Speeding up macro expansion

Early on, I saw several projects dependent on async-graphql and sqlx complain about slow build times. After profiling them, I found that macro expansion would sometimes take more than a third of that time. From my reading, I speculated that this was a relatively under-optimized part of the compiler.

Approaches considered and abandoned

Click to read my attempts before caching macro expansion.

I evaluated (and ultimately abandoned) a few approaches:

- Parallelize macro expansion: The compiler currently loops over macro invocations repeatedly until all names are resolved and nested macros are expanded from the inside out. While I believe parallelization is doable, nested macros and name resolution pose serious challenges to a naive approach.

- Apply the Watt runtime11 i.e. compile procedural macros to WebAssembly: I quickly realized that while Watt saves users from needing to compile procedural macros, it does not help with execution of those macros during expansion (and in fact incurs a slight performance penalty). Nevertheless, Watt pushed me to focus on macros modelable as pure deterministic functions.

- Cache the AST and “push” changes: Assuming small edits between builds, the AST (Abstract Syntax Tree) that represents a crate changes very slightly. Nevertheless, the compiler currently lexes and parses and expands from scratch.12 My vague idea here was to cache the AST from the last run, identify the code changes in the new version, and push those AST changes to the previous crate’s AST. This felt like it was on the right track but the devil is in the details:

- How would I represent “code changes”?

- What if the new AST is vastly different from the old one?

- Are parsing and lexing even time-consuming i.e. is there any benefit from caching them?

Caching procedural macro expansion

Finally, I landed at caching procedural macro expansion. The core idea is simple. Procedural macros take as input a TokenStream (representing an AST) and output another TokenStream. The compiler will cache this mapping from your current build; if the input is unchanged in your next build, it reuses that output instead of recomputing it.

This is far superior to “using release builds of procedural macro crates” mentioned before. For the vast majority of macros, instead of doing the same work faster, the compiler does zero work.

Side note: Side effects

Rust’s procedural macros are not necessarily deterministic “pure” functions.13 In other words, expanding the macro with the same input can yield a different output. The commonly used include_bytes macro, for example, reads the contents of a file. Even if the filename stays the same, its output will clearly change if the contents of that file change.

In practice, however, the vast majority of macros are in fact pure. This is the basis of the Watt runtime mentioned before and also the basis of periodic discussions on “const” proc macros.14

Augmenting the compiler

I needed to augment the compiler in several ways to support macro expansion caching. In particular, the compiler needed to be able to do the following:

- Skip pulling a macro from cache. As mentioned above, you may want to avoid caching some macro expansions in case they have side effects. I simply allow specifying these in an environment variable. In practice, I have yet to encounter a crate where I have needed to skip more than 3 macros.

- Hash macro (bang, attribute, and derive) invocations. The macro expansion cache is a hashmap, mapping invocation hashes to the expansions. As in the other areas of the compiler, I need to take care to use

StableHashes, so that the hashes are consistent across runs. On this, I avoided hashingspans (which represent positions in code) where possible because ideally the cache remains valid even if a new line of code pushes the code below it down a line. - Handle edge cases: duplicate invocation hashes, interpolated tokens15, and nested macros. All of these poses challenges to computing unique invocation hashes and consistent output ASTs. I typically flattened ASTs where possible and dropped un-cacheable ones where not.

- Serialize macro output. Luckily, I was able to leverage a lot of the data structures in place for incremental builds downstream in the compiler. Still, I needed to spin my own serialization mechanism since I am newly caching

TokenStreamsand ASTs.

Code snippet

If that felt vague, attached here is a code snippet of my core logic.

Click to expand a snippet from my actual code

pub fn expand_crate(&mut self, krate: ast::Crate) -> ast::Crate {

// ... Truncated ... //

let (mut krate_ast_fragment_with_placeholders, mut invocations) =

self.collect_invocations(AstFragment::Crate(krate), &[]);

loop {

let (invoc, ext) = invocations.pop();

// Gather newly discovered nested invocations and expanded fragments

let (expanded_fragment, new_invocations) = self.expand_invoc(invoc, &ext.kind);

invocations.extend(new_invocations.into_iter().rev());

}

// Insert expanded fragments into the crate AST's placeholders

// let expanded_krate = ...

let bytes = on_disk_cache.serialize(

file_encoder,

&self.invoc_hash_and_expanded_stream

);

info!(

"Cached {} bytes of macro expansion cache (holding {} invocations)",

bytes,

self.invoc_hash_and_expanded_stream.len()

);

expanded_krate

}

fn expand_macro_invoc(

&mut self,

invoc: Invocation, // holds macro invocation context

ext: &SyntaxExtensionKind, // holds the procedural macro callable

) -> TokenStream {

// ... Truncated ... //

let invoc_hash =

self.disk_cache.as_ref().and_then(|_| self.hash_item_no_spans(&invoc.kind));

let expander = ext.get_macro();

let tok_result: TokenStream = {

// 1. Perform lookup of the macro invocation hash in the new macro cache

if !self.should_skip_cache()

&& let Some(cached_stream) =

self.disk_cache

.as_ref()

.unwrap()

.try_load_query_result::<TokenStream>(invoc_hash)

{

// 2a. Pull from cache if it exists

debug!("Pulled from cache with hash {:?}!", invoc_hash);

cached_stream

} else {

// 2b. Else compute macro expansion from the proc macro crate

debug!("Not found in cache with hash {:?}!", invoc_hash);

expander.expand(self.cx, span, mac.args.tokens.clone())

}

};

// 3. Cache macro invocation hash with expanded TokenStream

self.invoc_hash_and_expanded_stream.push((invoc_hash, tok_result.clone()));

tok_result

}

Results

I have profiled my modded compiler against the default compiler, on several real-life Rust projects. Full details are in my rustc-profiles repo.

Below is a snapshot of those results (as of Mar 16, 2024).

| Project | speed up % | Default build time | Modded build time | Detailed analysis? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hedgehog | 40% | 19.3 s | 11.7 s | In rustc-profiles |

| polkadot-sdk | 35% | 30 s | 19 s | In rustc-profiles |

| brontes | 25% | 10.7 s | 8.0 s | In rustc-profiles |

| graph-node | 21% | 6.3 s | 5.0 s | In rustc-profiles |

| vector | 11% | 18.4 s | 16.4 s | In vector GitHub |

Proof by picture

As you can see in this rustc profile, my modded compiler expands only the procedural macros that were modified.

You can find the full-sized PDF here.

You can find the full-sized PDF here.

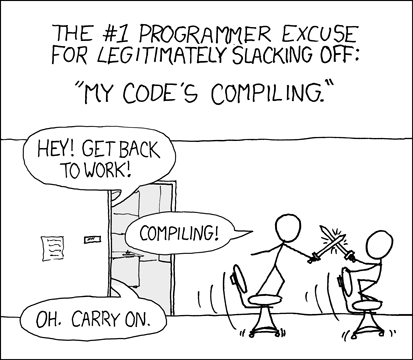

Now, I love sword fights on swivel chairs as much as the next guy …

But if you want to return minutes of your life with every compile, check out what I’m building at CodeRemote.

~ Kapil

Footnotes

-

https://corrode.dev/blog/tips-for-faster-rust-compile-times ↩

-

https://davidlattimore.github.io/posts/2024/02/04/speeding-up-the-rust-edit-build-run-cycle.html . I got to speak to David a few weeks ago, and learned he is hard at work building an incremental linker. ↩

-

https://benw.is/posts/how-i-improved-my-rust-compile-times-by-seventy-five-percent ↩

-

The parallel frontend is still only in the nightly compiler, ostensibly with plans to hit stable rustc in late 2024. More details are here. ↩

-

This is technically incorrect for a few reasons. Namely, inputs and outputs are

TokenStreamobjects, which are more like ASTs than raw strings. Also, attribute procedural macros take two inputs (the attribute itself and the body it is attached to) instead of one. Nevertheless, it is a useful mental model for the more detailed explanation here. ↩ -

Almost all of the compiler’s “frontend” (i.e. before the codegen phase) implements caching to drive incremental compilation. See more details on query-driven compilation here. ↩

-

https://github.com/async-graphql/async-graphql/issues/1287 ↩

-

Nicholas Nethercote has written several excellent blogs summarizing recent compiler improvements. In those blogs, he also has demonstrated some of the best tools to measure Rust compiler performance. His March 2024 blog is here. ↩

-

David Tolnay is the author of Watt. See more details here. ↩

-

During macro expansion, a macro transforms an input AST into an output AST. This AST is then inserted into the crate’s larger AST. ↩

-

https://internals.rust-lang.org/t/const-fn-proc-macros/14714 ↩

-

Interpolated tokens are embedded AST nodes. The source code itself deems them a “very strange” concept that the compiler team would “like to get rid of”. ↩